Introduction

Most smaller and medium-sized food and beverage and consumer goods companies generally approach their growth with a push-push strategy. The ones that are successful in the longer term are the ones that can ensure a sustainable product supply and evolve their operating growth model in the direction of market dynamics.

This step is essential to a 4Ps marketing model, which can be something other than brand savvy but fundamentally market-dynamics-conscious.

Beyond the initial traction, the first step in growth is laying the foundation for an efficient supply chain operation, which is a starting point.

The product supply view on growth

Contrary to what many believe, growth is challenging, especially in product supply. While it is a common belief that even exponential growth comes within a linear operational framework, it seldom does.

For example, many praise the launch of modern trade, known for its sophisticated ordering systems, as an organized way of working. Unfortunately, better ordering systems do not translate into efficient forecasts. It does not mean smooth orders across time. This does not mean that clients should submit orders within the desired timelines.

From a product supply point of view, growth means:

1) more orders, but also more diverse orders and so more complex orders

2) larger orders requiring responsive suppliers and an excellent working capital system.

3) increased frequency of orders and, therefore, faster reaction time.

Many small and medium-sized companies fail, not because their products need more traction in the market but because they cannot sustain the current growth levels. This can be due to delays, lack of product availability in the proper seasons or formats, lack of flexibility in production planning, or delays in the supply of components and raw materials.

If you are ready to push on the accelerator, ensure your product supply can sustain it. Of course, having products does not sell products. Hence the need for a commercial model.

The commercial view on growth

The three critical commercial vectors of growth in a commercial push-push framework are simple:

1) More clients/ more geographies

2) More distribution/ more points of sale

3) More products across existing or new points of sale

A sophisticated commercial organization has a seamless relationship with its customers and the customers of its customers. As a result, it can monitor stocks and depletion and understand whether the push approach stalls en route to the consumer. A less sophisticated organization can be surprised when a client with a positive orders trend suddenly stops ordering because it lacks that view of where the stock is stalling.

Working with modern trade is more difficult because understanding their dynamic often depends on expensive external data. Unfortunately, that data is necessary to paint a clear picture of the inventory, sales, and promotions and assess growth drivers and prospects.

First, market measurements address the fundamental question of numeric vs weighted distribution, with the latter being more important for growth as a catalyst for more purchases in the category. A critical commercial growth driver is to push-push toward better sale potential; therefore, more stores/sales points sometimes convert into more sales.

Moreover, even in a commercial view of growth, data like the share of volume in promotion, the share of shelf, average sales per store, and SKU velocity better prepare KAMs for their yearly negotiations.

What are the limitations of a commercial push-push model?

The approach hardly impacts the velocity in the store, purchase frequency, or reach. This growth method is essential and crucial, yet clueless about category dynamics like penetration, frequency of purchase, and over-reliance on TPRs and promotional activities, whether they drive baseline sales growth or load current shoppers.

The marketing view on growth

This growth approach, which falls short of building brands, focuses on category and in-market dynamics to understand where to invest and which levers to operate.

In the world of BASES and large FMCG market research departments, the volume of a consumer product in a given year is the function of:

Trial: the percentage of consumers who purchase the product at least once. Trial depends on many factors. First of all, awareness of the product. Consumers can only buy something they know exists. Many emerging products build awareness at the point of sale (where physical and mental availability overlap). Then, of course, distribution: the higher the distribution, the higher the purchase probability. The product appeal also plays an important role: the higher the appeal, the more consumers will want to purchase it. Promotions and activations also contribute substantially to trial by removing specific barriers, like pricing or usage understanding.

Repeat: the % of trialists who will re-purchase the product within the timeframe. Two essential elements contribute to repeating. The first one is performance vs. expectations: consumers are unlikely to re-purchase a product that does not satisfy their expectations. This is the post-usage value for money. When using or consuming the product for the first time, the Value for Money perception shifts based on the experience with the product. Sometimes, consumers are happy with the product but realize it is more expensive than they thought and decide to keep it from their basket of choice.

Purchase Frequency is the number of times the shopper/ consumer will buy the product in a year. Purchase frequency depends on the category dynamics, how much the shopper likes the product, and whether the shopper is convenience-driven. Convenience-seeking consumers prefer to shop for larger sizes by reducing the number of shopping trips within the category.

Volume per purchase is the average transaction size of a product. It is often related to purchase frequency considerations. However, PF and VPP will always depend on CEPs, such as consumption occasions and shopping missions.

So, what drives volume growth? Any increase in the above variable increases the business's consumption, but these variables cannot be picked randomly.

The Trial and Repeat Analysis

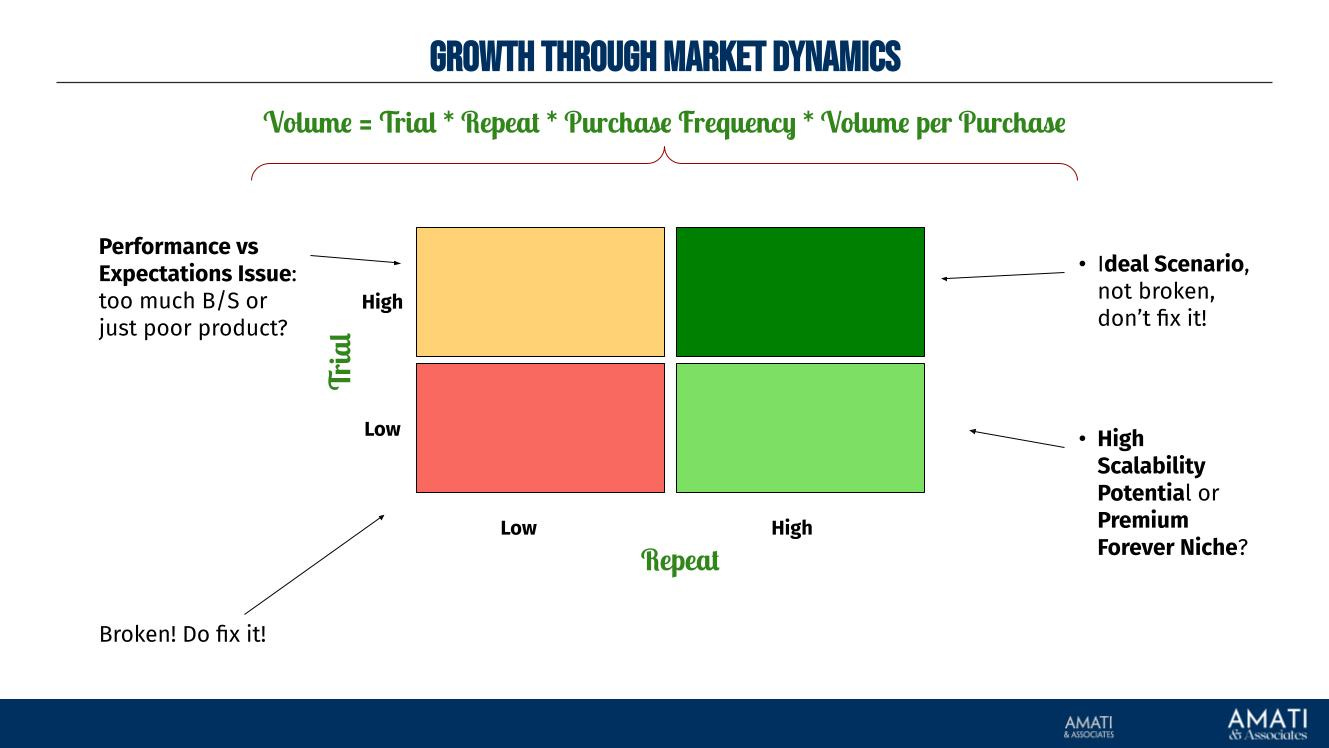

The first step is understanding the Trial and Repeat analysis, as the chart below exemplifies.

By mapping trial and repeat, four clusters emerge, and it is fundamental for you to assess where your products are:

High Trial, High Repeat: This is the dream scenario where many consumers purchase at least once and then repeat. Maintaining the status quo is a good strategy, both in terms of recruitment and distribution.

High Trial, Low Repeat: There is likely a disconnect between performance and expectation in this scenario. The product does not deliver against the promise or is over-promising (the famous Second Moment of Truth). In either case, the disconnect is with the product, which requires fixing. By redefining a promise that is more in line with the product, trial rates—which depend, among other things, on the liking of the product—will likely lower, but better repeat rates will offset them.

Low Trial, High Repeat: This is either an excellent product still in the development phase (low trial depending on lower distribution and awareness levels) or a very niche proposition that does a fantastic job satisfying consumers, hence the elevated repeat rate. In the first case, further distribution and awareness can drive growth; in the second, further distribution can be leveraged to increase trial.

Low Trial, Low Repeat: This scenario is difficult to assess. Sometimes, the trial is low because consumers do not know or understand the product, and therefore, they will not repeat it because they cannot comprehend what to expect. Other times, the trial and repeat are low because the product is niche at best and does not perform well enough to drive re-purchase.

So, what growth-driving actions can you take?

Before working on driving more distribution or growing awareness of your product, you need to understand how well your product repeats. Especially from a medium-to-long-term perspective, pushing the recruitment of new consumers will make no economic sense because you will not be able to retain them. Benchmark repeat rates in the category.

Are awareness and distribution not the culprits for low trial numbers? Is the product's appeal elevated enough to drive conversion? Or is there a benefit/price lowering its appeal? The answer to these questions is often the product's lack of credibility.

If you have a niche product with low trial and low repeat, moving beyond the scope of the current distribution might impact the overall liking of your product: Apple only listed limited, less-premium items at Walmart because they knew that committing too many SKUs to that partnership would damage them cross-channel.

Monitor your promotional activities. Repeat is driven by performance vs. expectation and post-consumption pricing. Aggressive promotions and sampling lower the VFM barrier but might not translate into long-term repeat.

When driving distribution, continually invest in WD, not numeric. Distribution costs money and effort, so make sure it has potential.

Can you impact your growth with purchase frequency and volume per purchase?

The traditional view wants purchase frequency and VPP intrinsic to a market and a category. A category would have ranges of PG and VPP that will not significantly change. This is true when you consider the number of meals people have or mops they buy in a year(!).

From the marketing point of view, Category Entry Points, which are consumption occasions and shopping missions, will come to the rescue: most men shave every day. They are likely to use the same quantity of shaving cream; therefore, the amount of the product they need, but in a year, is fixed in theory. However, if they often travel for work, they will require a specific travel format for shaving cream due to air travel restrictions on container sizes. So for those occasions, those men will have extra shopping needs. By tapping on extra occasions or shopping missions, marketers can overcome the limitation of category intrinsics and drive growth beyond them.

The previous is an example from the demand side: regulation comes in place, and it generates demand for a specific format of shaving cream. There is also an example from the supply side: Grand Marnier has created a ritual for consuming its products by cooking the traditional French pancake. By doing so, it has grown beyond the intrinsics of the triple-sec liqueur category. Likewise, limoncello as a category is experiencing a second renaissance, and the yellow liqueur has become a pivotal ingredient in an alternative spritz in the UK, well beyond the boundaries of Italian restaurants and its digestive category intrinsics.

This approach is at the core of developing new formats and flavors to tap into more CEPs: the almighty line extension. Some line extensions are specifically designed to recruit a defined demographic or provide more consumption occasions.

In a nutshell, Line extensions are extensions of a parent brand in the same category as the parent. Line extensions include new benefits, flavors, formats, and more. These brand extensions can tap into consumption occasions or different shopping missions. The shaving cream example is a line extension. On the other hand, the examples of spirits are based on consumption occasions and do not require dedicated SKUs. Line Extensions are not riskless enterprises!

In Conclusion

In conclusion, the growth of small to medium-sized food, beverage, and consumer goods companies hinges on the interplay between efficient supply chain management, commercial strategy, and market dynamics awareness. Sustainable product supply is crucial, as growth often brings complexity and higher demands. Companies must ensure their supply chain can handle increased and diverse orders to prevent market failures. On the commercial side, expanding client bases, distribution points, and product ranges are essential but require sophistication in data analysis and tracking. Marketing efforts are the ultimate and most efficient growth approach; companies can prioritize their investments by focusing on trial and repeat dynamics. Leveraging Category Entry Points through strategic line extensions can drive growth by tapping into new consumption occasions and shopping missions.

A balanced and evolutionary approach that integrates supply chain efficiency, commercial strategies, and marketing toolboxes is vital to achieving sustained growth and market presence.